Dead reckoning for startups

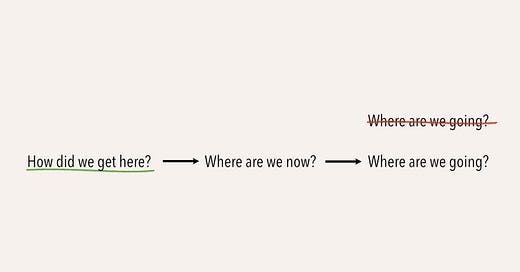

Answering the question "Where are we now?" by first asking "Where have we been?"

I’ll be honest: I’ve spent a week thinking about this post and I’m still not satisfied. I feel twisted into knots. We don’t think enough about the past. And we don’t revisit the paths not taken. And it’s hard to correct for that. So what?

But I’m convinced there’s something here. Hopefully you’ll humor me when I revisit these ideas — ideally with greater clarity! — in the coming months.

Dead reckoning

“How did we get here?”

I kept thinking of this question after listening to an extraordinary interview of the explorer Wade Davis. Among many other things, Davis has studied how Polynesians navigate the open ocean:

They can sense the presence of distant atolls of islands beyond the visible horizon just by watching the reverberation of waves across the hull of their sacred canoe, the Hōkūleʻa, this great vessel that is a symbol of this Polynesian renaissance. In the darkness in the hull, they can distinguish as many as five different sea swells, again, moving through the water, distinguishing those caused by local weather disturbances from those that pulsate across the ocean and can be followed with the ease with which terrestrial explorer would follow a river to the sea...If you took all of the genius that allowed us to put a man on the moon and applied it to an understanding of the ocean, what you would get is Polynesia.

While the captain looks ahead, the navigator sits on the back of the canoe, looking into the past, foregoing sleep, keeping track of each twist and turn to answer the question, “Where are we now?”

Here’s Davis again:

The amazing thing about this tradition was that it was based on dead reckoning, which means that you only know where you are by remembering how you got there. And it was the impossibility of doing that that kept most European transports hugging the shores of continents until the British solved the problem of longitude with the invention of the chronometer. But we know that 10 centuries before Christ, from an ancient civilization called Lapita, the ancient ancestors of the Polynesians set sail into the rising sun. And this idea of dead reckoning means, and back to your navigator, why he’s not running the ship, because he or she must sit monk-like on the back of the vessel, remembering every shift of the wind, every tack, every sign of the sun, the moon, the stars, the birds, the salinity in the water, every one of these empirical observations, and the order of their acquisition. And if that memory chain is broken, the voyage can end in a disaster. And all of this has to be done by an individual who lives in a civilization that lacks the written word. So all of this has to be placed in memory over a three- and four-week voyage. Think about that. Tell me that is not a form of genius.

Dead reckoning is navigation by relative estimation. The navigator knows where they started; then, once underway, they make regular estimates of distance traveled and direction; between the known starting point and the cumulative estimates, they can infer where they are.

It’s a way of answering the question “Where are we now?” just by knowing where we’ve been.

Drift

The biggest shortcoming of this method is obvious: What if your estimates are wrong? With each turn, your errors compound. Before you know it, you’re wildly off course with no way to recalibrate your location. (The speed with which errors compound is known as the “drift rate.”)

Worse yet, there’s no way to correct the errors. You can’t retrace your route, find the error, fix the math, and recalculate. You’re just lost.

You’re forced to search for some new signal of absolute, rather than relative, position to restart your calculations. (This is what it feels like to be at a startup without product-market fit, desperately grasping for even a single strong customer signal from which to recalibrate your position and calculate a new path.)

We rarely navigate by dead reckoning. GPS can give us something functionally equivalent to absolute positioning most of the time, and it’s much more reliable than relative estimates subject to drift.

There are exceptions, though. Pilots navigating under extreme conditions often rely on inertial navigation systems that perform a high tech version of dead reckoning. Submarines, space ships, and planes rely on these systems. And in a way, so too do startups.

Navigating a startup has much more in common with piloting a submarine or a space ship than it does with driving a car. You have very few wayfinding markers out your window. You’re looking through a little porthole, the edges of the map are blurry at best, and you’re discovering new features as you go. The signals you get are murky and largely relative — “more of this” or “less of that” or “head in this direction” — instead of lat-long coordinates or mile markers.

Oracles

Yet we assume we know where we are.

Of course, this isn’t a safe assumption. We’ve been navigating by dead reckoning. We should take the idea of drift much more seriously than we do. Each mistake compounds into next week and the week after, taking us further off course. But we rarely revisit those decisions to ask, “What if we were wrong? Where has that led us? Where the hell are we, anyway?”

It’s not that teams don’t realize they have this blind spot. They know. It’s just hard to look off the front of the boat and off the back at the same time.

While most of the team looks into the future, a few long-tenured navigators tend to look into the past. Whenever the broader team senses they’ve gone off course, they come to these navigators and consult them, like oracles. “Tells us where we are,” they ask, “by reminding us where we’ve been.”

Usually there’s an engineer who remembers the key architectural choices and their alternatives, a data analyst who remembers a critical but long-forgotten A/B test decision, or a marketer who remembers the origins of a big campaign idea. You know these folks. They remember the paths not taken. They’re essential. Without them, we’d have a much blurrier picture of where we are now.

What next?

It’s not easy to fight the bias of looking forward instead of back. None of what follows is revolutionary, but here are a few ideas:

When presenting a new idea, instead of justifying it by telling a story rooted in the present, pick a point in the past and start there. Work your way from the past to the present. Treat each step as a link in a chain.

Formalize important decisions with an emphasis on paths not taken and why. Teams tend to forget the alternatives that were taken seriously. It’s really hard to recreate your state of mind in the past, so try to write it down.

Log critical decisions in a company-wide calendar. Every org has something — a Google Sheet, notes in dashboards, whatever — that tracks partial history. Try to formalize the process and share the result widely. (How does this not exist as a feature of any system of record tools?)

Present most data over a longer time horizon than feels comfortable. This gives some context for major historical changes, and puts recent swings in context.

Introduce case studies into new hire onboarding. Use a couple of important past events to tell a story about how the business works and why. This is as true for cultural decisions (what are some company values we explicitly didn’t choose?) as it is for business decisions.

Reward the navigators and historians. Most of the folks I’ve met who play this role are implicitly valued, but largely ignored by the organization’s formal power structures because one’s interested in the past and the other in the future.