Don’t compete with your forebears; collaborate

How working on my dad's autobiography helped me appreciate shared play

Almost exactly three years ago I had one of the best ideas of my life.

Events, at the time, were not going according to plan. Anna and I were hunkered down at her parents’ house in Rhode Island as Covid began cascading through the US. We’d left New York weeks earlier — not because of early signs of the pandemic, but because it was time to start the year of travel that we’d been planning for months. I’d given up my job. We’d given up our apartment lease. We’d bought plane tickets to Spain and booked Airbnbs in Morocco. Movers had loaded our stuff into a van and we’d driven through the ghostly streets of Manhattan and then we’d settled into my in-laws’ old farmhouse on the edge of the woods, trying to keep ourselves busy with walks and Peloton rides and elaborate home-cooked meals. We were waiting for a “return to normal,” whatever that meant.

Every night I’d call home to hear how my parents were doing. My dad was calm but exhausted. For the last decade he’d been the primary caretaker for my mom as Alzheimer’s had slowly ground her down, and the abrupt isolation of the first month of Covid had tipped her into the final, terminal stage. My dad had no help in sight. The virus made everyone a threat to everyone else, so the aides who had come to the house several days a week now stayed away. It was a grind and there was little I could do.

Daily calls that were meant as a lifeline ended up reinforcing a feeling of helplessness. Pretty soon each conversation sounded the same. “That new CDC report looks worrying.” “Your mother had a setback today.” “Did you see what Trump tweeted this morning?”

We had to change the script. “Why don’t you write an autobiography?” I suggested. ”You write something every day, and then we can talk about it at night. I’ll handle getting everything laid out and printed.” This was meant to be a small idea, but it turned into a big one.

The idea hadn’t come from nowhere. My dad’s dad had self-published an autobiography later in his life, less than 100 pages, and shared it with his family. I imagined something similar, short and sweet. I thought of the book project as a short-term hack: Mine the past for new material that could replace the daily repetition of Covid and Alzheimer’s.

The first few weeks of working together were difficult. My dad began by writing isolated vignettes from his life: Hearing about Sputnik on the radio while he worked at the local pool as a teenager, attending a white tie gala with a German date as a graduate student, the inconsistencies of electrical plugs in England (yes, really). There was very little narrative, and very little of him, to tie it all together.

But every night we had something new to talk about. And every night I was able to ask, “Why did this little moment in your life strike you as memorable?”

Day by day, more of him made it onto the page. The capacity for intense focus noted by a child psychologist. The excitement of boarding a boat to leave the United States for the first time. The uncertainty of itinerant employment during the mid-1970s. The feeling of failure after the dissolution of his first marriage. Eventually, finally, how he made sense of taking care of my mom, who passed away about a month after he started writing.

The project gave me a much deeper understanding about what made my dad tick. But it also gave me much more insight into what made me tick, at a time when I really needed it. That intense focus my dad had as a child, his delight in synchronicity, his quiet moral streak — that was me, too. There weren’t just threads through his life, but a clear thread from his father to him, and from him to me. In a way, the decisions my dad had made though his life were decisions a part of me had made.

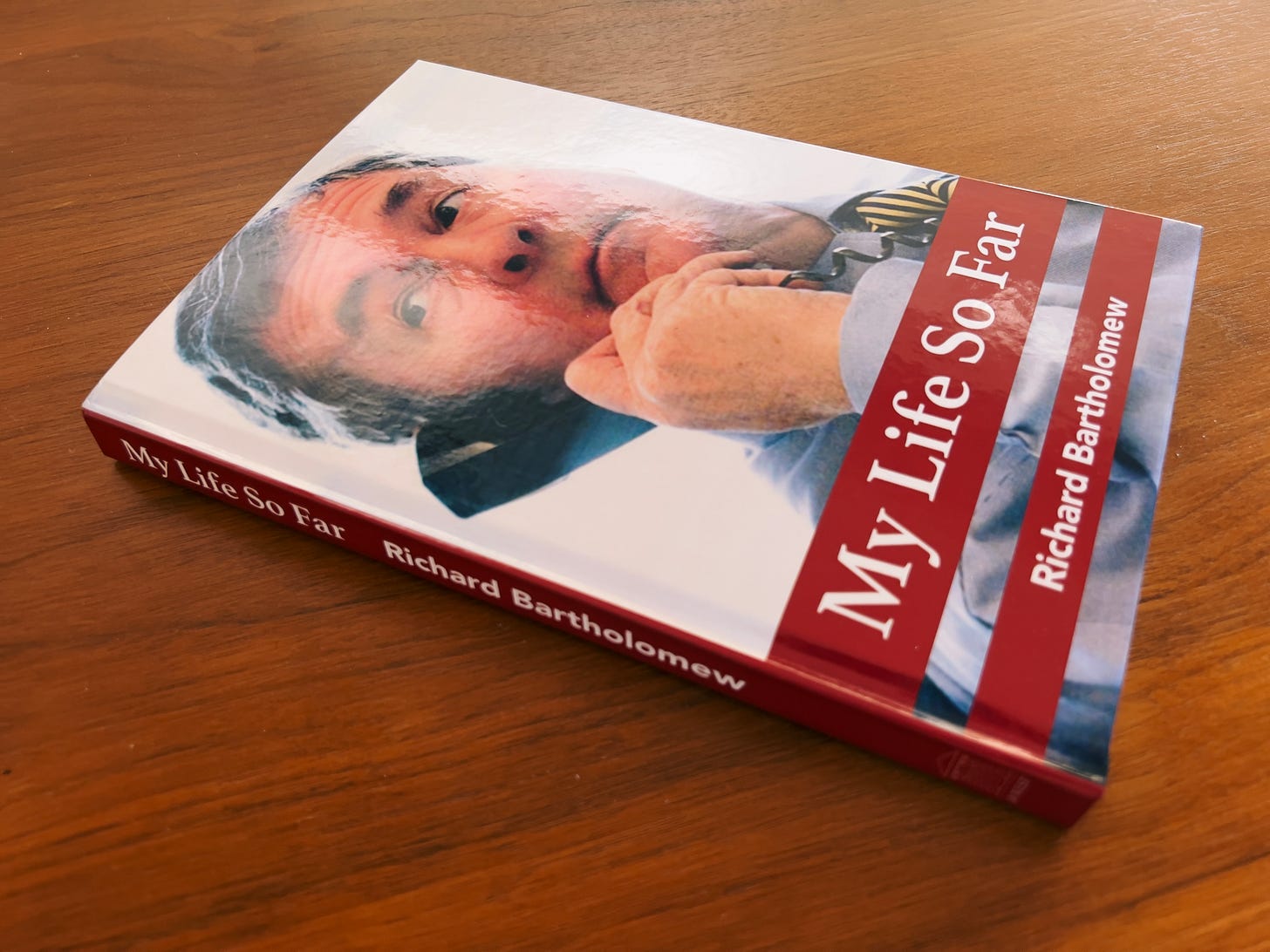

We printed the first copies of the book seven months after starting. My dad gave them as Christmas presents to family members. But he also walked around his neighborhood, handing them out in person to his friends. And he put them in the mail — his German date to the white tie gala almost 50 years earlier got a copy in her mailbox in Seattle.

What happened next was a total surprise. His friends who got the book took it as an invitation to talk about their own lives. He reconnected with friends from decades earlier. Suddenly a project that had started as a distraction became an excuse to catch up or delve deeper. The printed book wasn’t the end, it was the beginning.

I’ve been thinking more about my dad’s autobiography this week because I’ve just read the classic Finite and Infinite Games.

James Carse’s starting premise is simple: “There are at least two kinds of games,” he writes. “A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.” From this distinction he unspools an entire philosophy for living.

There’s a reason why this book pops up over and over among independent workers. Carse takes a deep interest in boundaries, and when to accept or question them. He sees the clear connection between the rules we play by and the identity we inhabit. Independent workers must grapple with these questions in a way many others don’t.

Carse shows us how to interrogate the games that we’re playing, and to ask whether we accept what the rules of those games do to us. Do the games of corporate America, with their attendant titles and promotions, make us better? Do the games of status and more, more, more make us happy? Are we playing by rules that are rooted in competition or collaboration?

The piece that hit me right between the eyes is Carse’s emphasis on surprise:

Surprise in infinite play is the triumph of the future over the past…Because infinite players prepare themselves to be surprised by the future, they play in complete openness. It is not an openness as in candor, but an openness as in vulnerability.

That’s what the autobiography was: A shared act of vulnerability between me and my dad. It was an act of opening the door to the future. It has produced surprise after surprise.

So many of the people I know see their family histories as fixed, complete, finite. Rather than taking history as a starting point, as an invitation to collaborate, they see it as a competitor in a finite game. Their predecessors must be outdone, ignored, defeated. They must be made proud, proven right, satisfied.

But I think this framing has it all wrong. History is an invitation. The game has no end. There are no winners and losers.

Don’t compete with your forebears, collaborate with them.

This week’s recommendation is an interview with Spike Eskin, the cohost of The Rights to Ricky Sanchez, a podcast about my beloved Sixers, and oversees programming at WFAN in New York. Though this interview has some sports-specific conversation, it is not an episode about sports. Instead it is about the media landscape, the traits of a great media personality, and what makes for compelling friction.

To more surprises!