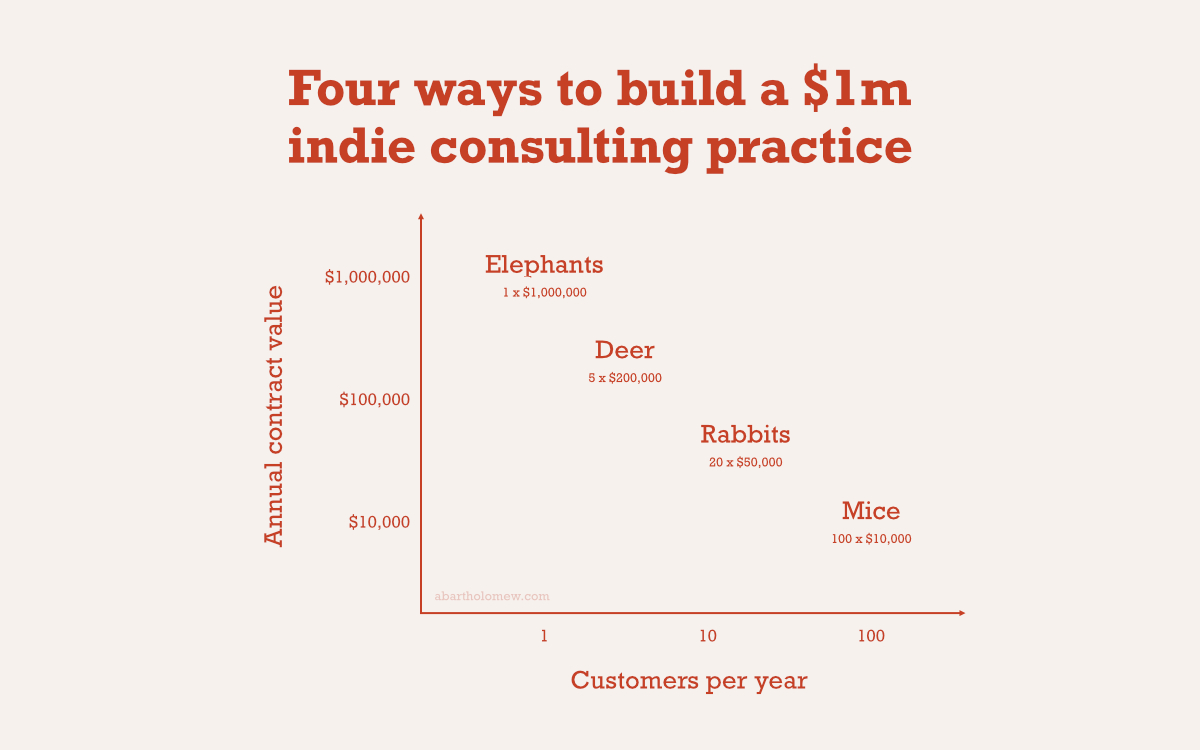

Four ways to build a $1m indie consulting practice

Respecting the balance between offering, price, and acquisition motion.

Five Ways to Build a $100m Business might be the post I cite most often to startup folks. The conceit is straightforward: To get to $100m, the number of customers you need is proportional to how much each customer pays you.

By extension, how much each customer is worth will determine how you acquire each customer. If you need a hundred million customers worth $1 each, free viral growth is the only plausible way to go; paid marketing, much less salespeople, is not an option. But if your average customer is paying $1m, expect lots of expense reports for steak dinners.

This sounds so simple, but it can be easy to lose track of. Especially in the early stages of building a business, product, customer value, and acquisition motion are in constant conversation with each other. The product is a moving target and customer values might be inconsistent or unpredictable, which makes it hard to settle on the right go-to-market activities. You may want bigger customers but only have the product features to serve smaller ones — should you build the sales motion for the customers you want tomorrow or the ones you can win today? Or let’s say you win a bunch of those smaller customers, but as the product gets more mature you start to target the bigger ones — and find the tactics that worked for acquiring smaller customers don’t work for big ones?

Indie consultants face similar questions and tend to fall into similar traps. So I thought I’d adapt the frame: Here are four ways to build a $1m indie consulting practice.

Elephants: One $1m client

I haven’t had a million dollar a year client (yet!), but they definitely exist. Maybe a shadowy businessman needs to eliminate a rival with a single sniper shot from a great distance. Or less cinematically, a hedge fund is looking for hands-on, highly technical expertise to support a multi-billion dollar deal.

No matter what, snagging a million dollar client means you possess a very specialized skill. Your client will likely see you as their only option. Your client is also probably in a field that is amenable to financial leverage; otherwise, it’s hard to see how a single person could deliver $1m in value.

This is a tough matchmaking problem: A rare problem in need of a rare expert. Deals will be won almost exclusively on word of mouth, since verifying your expertise will be very hard for non-experts (your clients) to do. You’ll be totally illegible to the outside world but a known quantity in the tight communities that represent your clientele. You’ll do zero marketing. Instead, you’ll do extremely high-touch, long-term relationship building in niche markets. Dealflow will be erratic.

Once a client knows you’re the best and only option, you’ll be interviewing them more than the other way around. You will be very choosy about the clients you take on because your reputation depends on it. You probably disqualify the large majority of folks you talk to, and even still you only need to have a dozen or fewer prospects a year.

Deer: Five $200k clients

These clients take two common forms. The first is extremely high-value project work — like elephants, just a little less so. Relative to the elephant hunter, the deer hunter either will be in a less specialized field or will accept a wider range of potential gigs.

The second is fractional executive work. It’s easy to imagine a fractional CTO, for instance, who gets paid $200k for six months of half-time work. The cash pay is higher than full-time market salary, but in exchange there may be no equity, no benefits, little loyalty, no long-term ownership, and more chaos within the company. Many companies see this as a good trade in order to fill a role more quickly, or with someone more senior than they’d be able to afford full time.

Closing deals here is still highly personal and consultative. You might do a little marketing — an email newsletter, a conference, posting on Linkedin or whatever — but most of your effort will be on cultivating a tight network of CEOs, investors, and executive recruiters who can recognize high-value talent and are able to pay for it.

Rabbits: Twenty $50k clients

The jump from deer to rabbits is the critical breakpoint. You’ll shift from a sales orientation to a marketing orientation. Acquiring twenty clients a year is much harder than acquiring five. You’ll try to solve this by standardizing what you offer, how you price, and how you sell, because you can’t afford waste when you need so many reps.

Standardization helps in three ways. First, you can put out a consistent marketing message. A standard offering translates much better to broad communication. Second, standardization ensures that most conversations are with qualified prospects who know what they need and what you offer. You’ll spend less time in discovery and less time talking to unqualified prospects. And third, it allows you to build some repeatability into how you serve clients once you sign them. This is the level at which you have to really “productize” your offer. You’ll sand the rough edges off your positioning, your processes, and your pricing.

The challenge is that this standardization invites competition. You’re suddenly legible to the market. No rough edges means your message might not look so different from someone else’s. And a highly repeatable process is one that can often be copied. So you have to work really hard to position yourself as “the best” rather than “the only.” Being “the best” is much harder than being “the only.”

Mice: One hundred $10k clients

Just as elephants are a more extreme version of deer, mice are a more extreme version of rabbits. Signing two clients a week, every week, to five figure deals is damn near impossible.

For one thing, delivering $10k of value in under 20 hours is very hard if the help you’re providing isn’t highly personalized. But with the exception of coaching, it’s hard to build space for personalization when you’re bringing in two new clients a week. At the risk of mixing rodent metaphors, you’re stuck on a hamster wheel.

Ways to fight the constraints

Hire people

If you’re acquiring Rabbits and Mice but running out of time, one way to keep growing is to hire folks to help. This is possible because, in serving Rabbits and Mice, you’ve probably built some repeatable processes that you can teach to others. Outsourcing the work will allow you to take on more clients, but it will also further undermine your differentiation, and it will ratchet up the speed of the customer acquisition hamster wheel. Or as the cyclist Greg Lemond said, “It doesn’t get easier, you just go faster.”

Honestly, unless you have plans to build a big team, hiring a few folks is a trap. I’ve had a bunch of friends burn out this way. You end up spending most of your time selling instead of doing the work; you compromise the types of work you take on in the interest of keeping the team employed; and you live in fear of having to let people go if you can’t find enough work. An even bigger team doesn’t solve this problem, but it does make it a little easier by at least allowing you to further diversify your client list.

Sell something other than your time

This is like going from Mice to Flies — take the streamlined advice you’re already giving and turn it into content, classes, or a product. As with hiring people, you’ll have to spend more and more of your time marketing, but unlike hiring people, each incremental sale doesn’t require more effort from you. Of course, at this point you’re no longer a consultant and no longer providing personalized advice — you’re a “creator.”

Get paid in equity

Rather than taking cash, you can take equity. Most of the time the equity will be worth less. But every once in a while it won’t, and if a few of your clients hit it big you can end up making substantially more than if you took cash. For what it’s worth, I tend to take cash instead of equity. It’s hard enough finding clients with interesting work — to then have to disqualify some of them because you’re unsure of the value of the equity makes things even harder.

Most indie consultants aren’t trying to build a $1m practice

Most businesses aren’t trying to make $100m a year, either. This is by no means a criticism. The deli down the street is comfortable with what it is, and of course it can still be a good business for the owner without aspiring to “venture scale.” The same is true for consulting practices.

That said, thinking big can reveal what’s holding you back at much smaller scale. The ideal balance between price, acquisition tactics, and offering is going to be pretty similar whether you’re making $75k a year or $750k.

You can mix and match, but a primary focus helps

In 2024 I had clients who paid me four figures, five figures, and six figures. But my overall approach is oriented around the six figure clients. I like the high-touch, context-intensive work. I treat the lower-cost clients as exceptions rather than the rule. Among other things, this helps me feel comfortable doing very little marketing, because I’m not trying to build a business on rabbits or mice.

Our impressions of how indie consulting looks is biased toward the folks who hunt flies and rabbits

When I first started consulting I got a lot of advice that really only made sense if I was hunting rabbits. I should post all the time on LinkedIn; I should specialize; I should price on value rather than time; I should build a big funnel. None of this makes sense given my typical client pays me over $100k. They’re paying for my attention, not some product I’ve made.

But it’s easy to see where this well meaning advice was coming from. The consultants hunting rabbits and mice are highly visible because they have to be. (Those hunting elephants and deer are not because, let’s be honest, who would post to LinkedIn if their livelihood didn’t depend on it?) The Availability Bias strikes again.

If I ask you to think of a bird, you’re going to think of something common — a robin, a bluejay, whatever. But there are almost 20,000 species of birds, and some that still remain undiscovered. You don’t have to be a robin or a bluejay. You could be a pennant-winged nightjar, or a golden fruit dove, or a bald parrot, or an African finfoot, or…whatever fits a sustainable niche, no matter how strange.

Examples welcome

This post is, unavoidably, an oversimplification. I’d love to hear examples of folks who are breaking some of these constraints in interesting ways, or common work archetypes I missed inside the Elephants-Deer-Rabbits-Mice examples. Just reply to the emailed post or leave a comment on Substack.

Closing recommendation

Most of my music discovery happens via playlists curated by someone with good taste. Dinner Music Weekly is a great one. (Here’s the Substack, and here’s the playlist on Spotify.)