Last weekend Anna and I were talking about the harbor near our house, and the small channel that separates our side from the other. Our friends had considered kayaking across to meet us for dinner. I imagined a children’s book about a family of mice, riding on the back of a duck to the other side to meet their distant cousins.

I saw the story as a map. Since I’ve become a hobbyist cartographer, I see almost everything as a map.

Mapping is the ideal fit for my data skills, design interest, and spatial mind. (Once the son of an urban planner, always the son of an urban planner.) I spend my mornings sifting through government websites and cleaning up messy data files and making lighting choices in 3D modeling software. I listen to podcasts about maps and browse historical maps of the places I travel and bookmark maps I love. It’s nerdy fun.

Map making is a process of noticing. It’s a process of exaggeration and elimination and abstraction. It’s a process of deciding what to communicate and how.

But what even is a map?

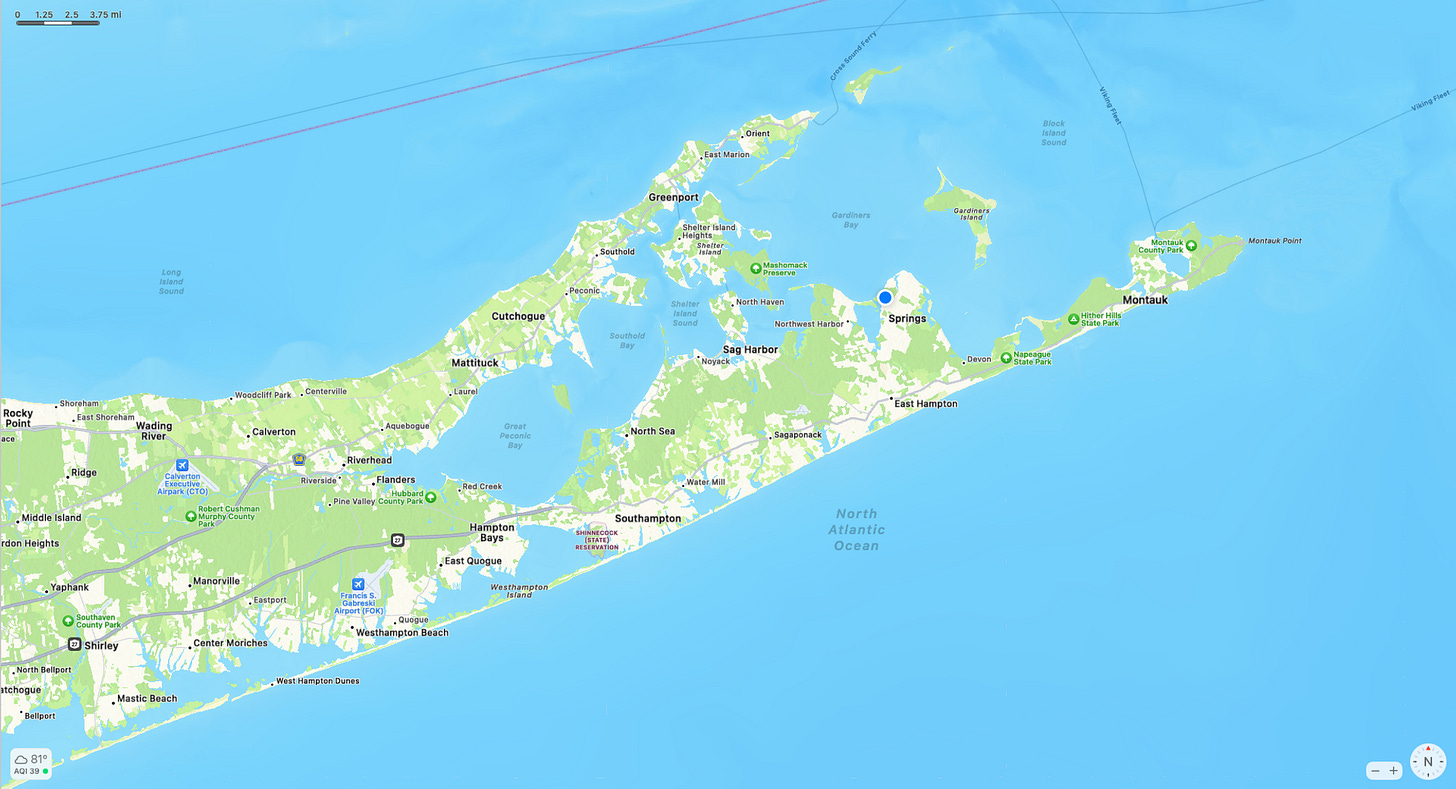

This is a map, obviously:

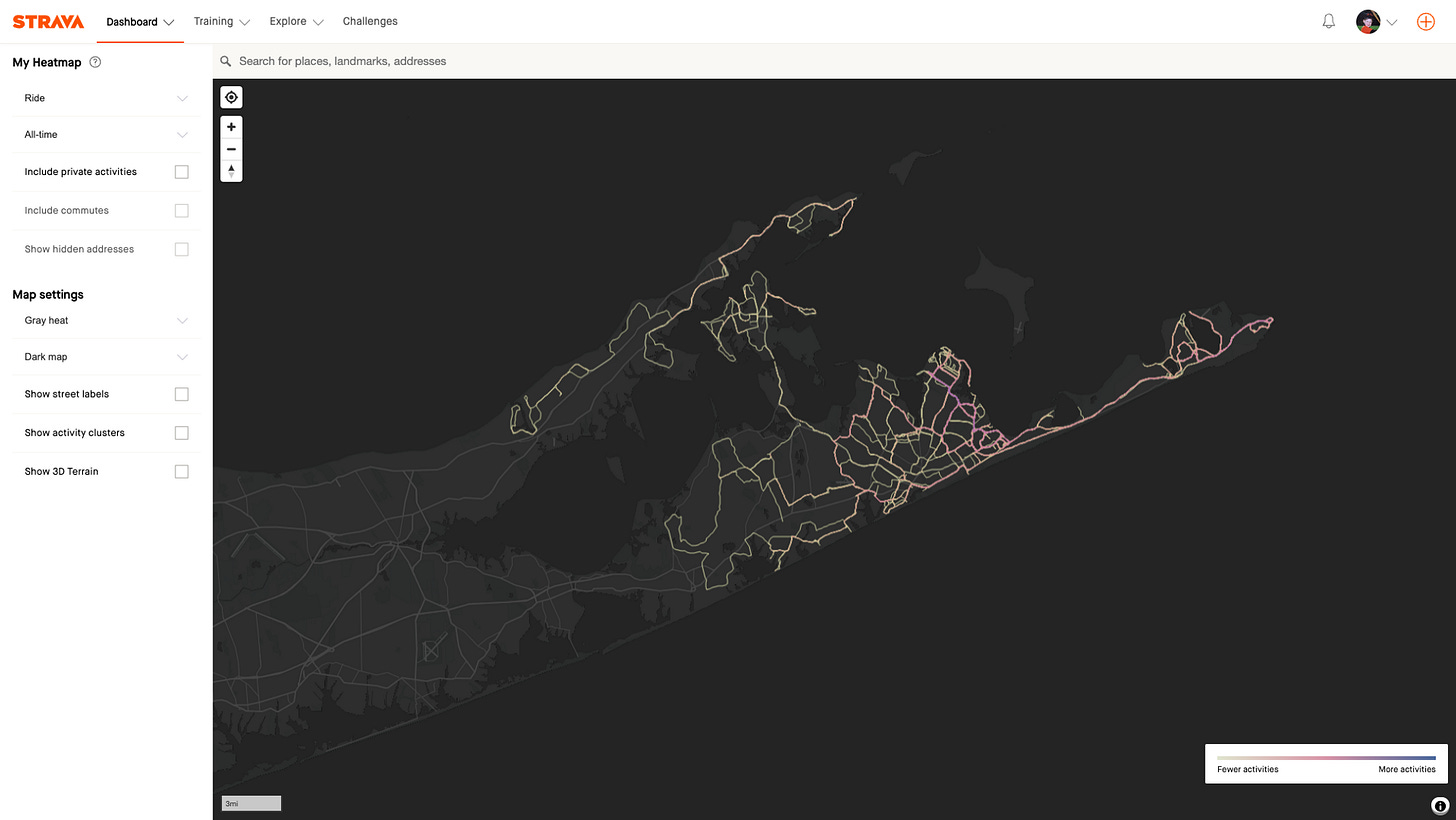

So is this, an artifact of my cycling habits:

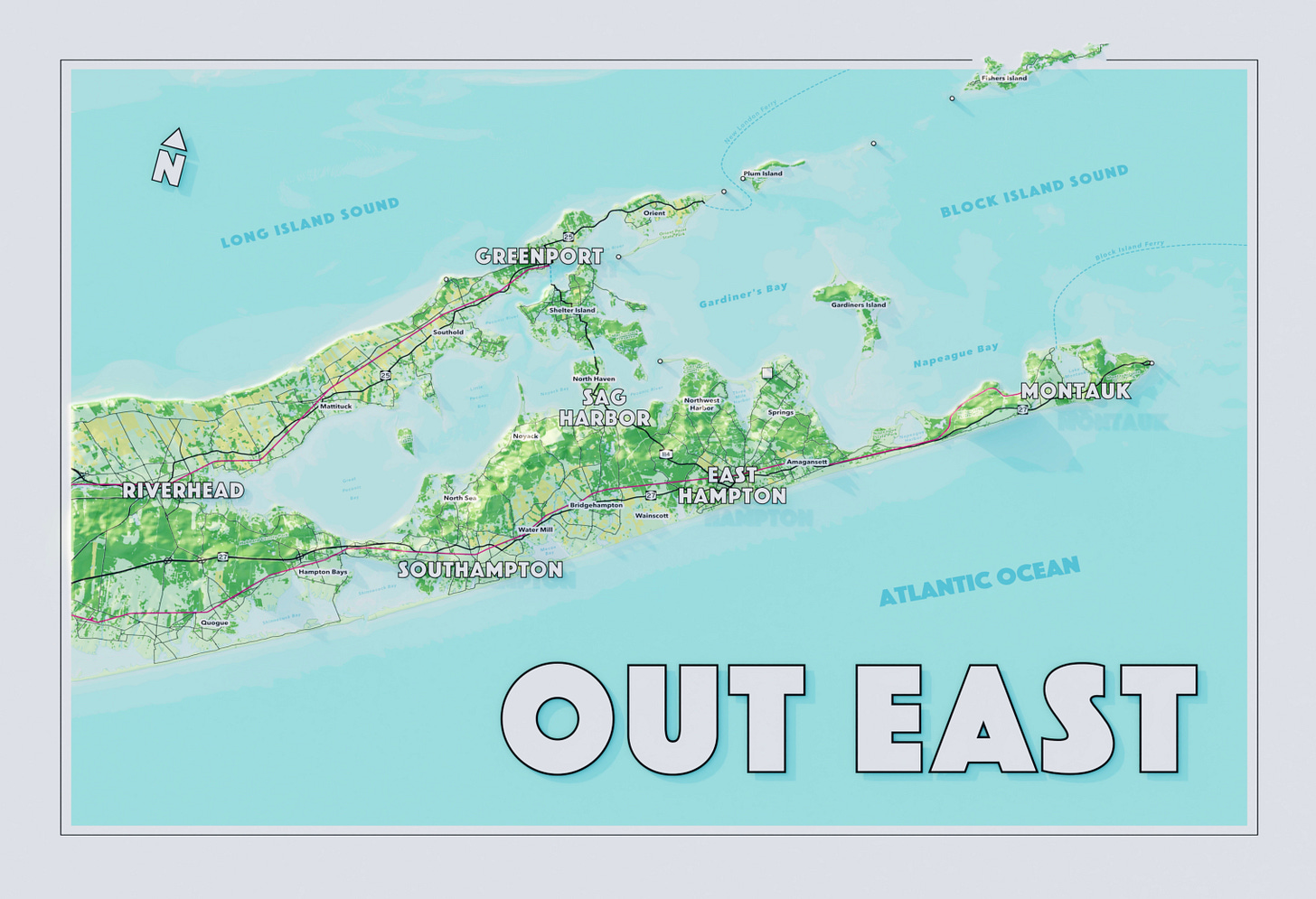

And this, which I recently made:

Of course, something doesn’t have to look like a traditional map to serve as a map. A human palm can be a map, if you’re a fortuneteller: “This is where you’ve been. This is where you are. This is what’s in your future.”

A line in the sand can be a map: “This is where I am. This is where you are. This is the thing between us.”

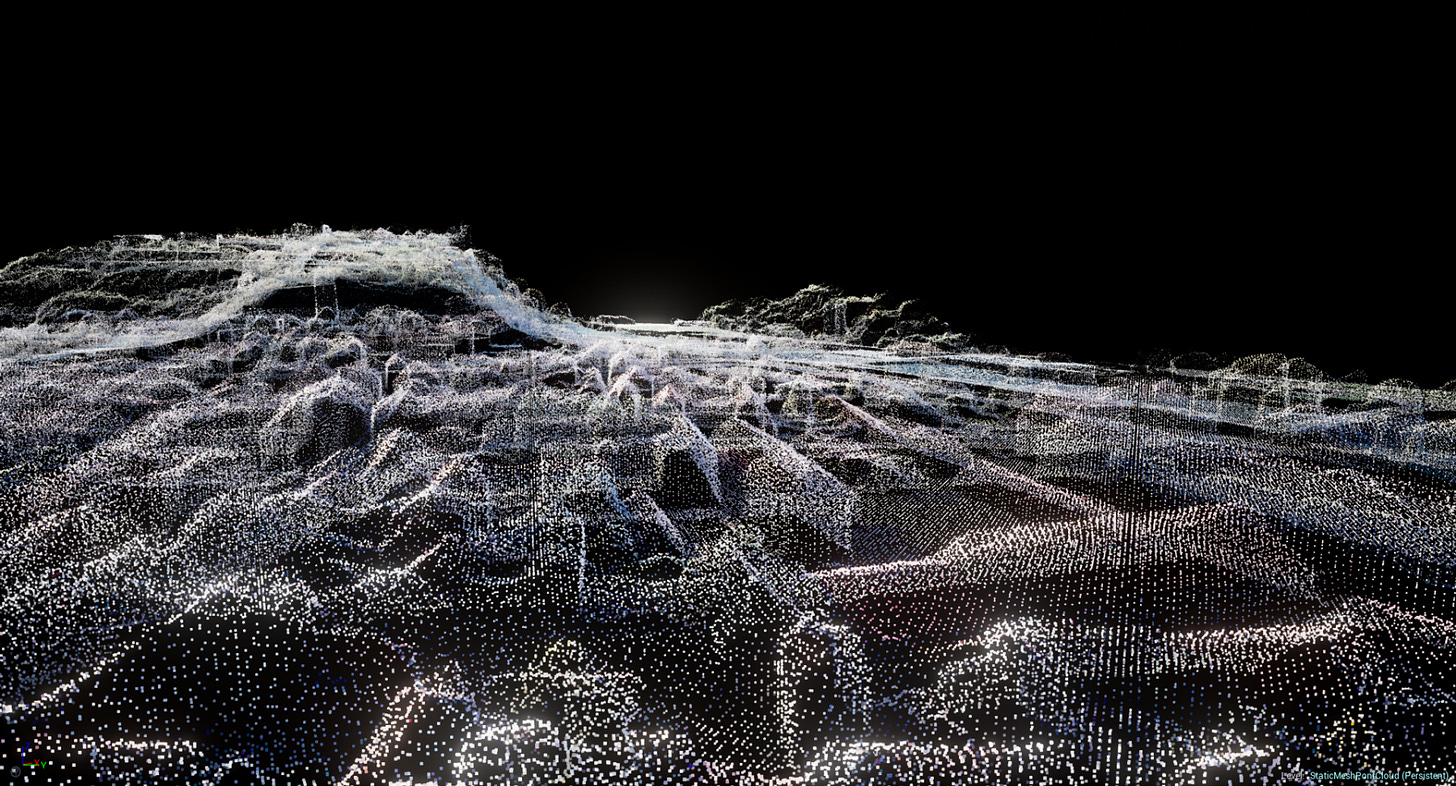

But these lines in the sand are not a map:

Lidar data is not a map, even though it may show where things are.

A valley is not a map, even though its walls may tell us where glaciers have moved and where the soil is right for trees.

A railroad is not a map, even though it may hint at how to get to the city or the route to a nearby mountain pass.

Few things are maps, but almost anything can be a map. A palm isn’t a map until it is, because someone decides to use it that way. Almost any object, when used to demarcate space or time or direction, can become a map.

The difference is intention. Maps are meant for communication. They presume an audience and a purpose. They tell us what to notice and, by exclusion, what not to. They contain a story, or many stories, by design.

Mapmaking requires paying close attention. With maps on the mind, I’ve started to notice new things. Everywhere I look I now wonder, “How could I make this into a map?”

I’ve had this experience a few times before. When I was first learning to code, I occasionally dreamed in code. When I first practicing photography, I saw everything as a scene to compose. I noticed the quality of the light and the small details of human interaction.

This cognitive restructuring is one of the unique pleasures of practice. Do something enough and it’ll begin to change how you see the world. Keep practicing, and the changes will stick, below your level of awareness. It’s only when you pick up a new practice that you notice the feeling of seeing things differently again.

This week’s recommendation is an interview with someone who works on Apple Maps but is perhaps best known for a census he and a team conducted of squirrels in Central Park. Nerds only — this is pretty niche content.

Insightful as always, Andrew! Two potential links of interest - (1) https://www.abhishekn.com/publications-all/the-economics-of-maps (2) https://slate.com/culture/2012/01/the-best-american-wall-map-david-imus-the-essential-geography-of-the-united-states-of-america.html ... We have a copy of the latest Imus map in our home!

Very interesting - thank you Andrew. Listening to the Nat Slaughter podcast now.

This book is good re your last point about cognitive restructuring. Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes

by Alexandra Horowitz. She takes a walk around the same city block with eleven different experts. https://bookishramblings.wordpress.com/2014/01/20/on-looking-eleven-walks-with-expert-eyes-by-alexandra-horowitz/