Smelly Words

Certain phrases have a stink to them

“Can’t miss.” “Inspired by a true story.” “Made with natural flavors.” These phrases make your nose wrinkles instinctively. Something’s off.

Though most business jargon has an almost antiseptic smell, I’ve become a lot more sensitive to the phrases that betray some sort of underlying rot. I hold my nose and lean in for a closer inspection. Something stinks — but why?

Today’s malodorous phrase: “North Star Metric.” I can’t tell you where the phrase originated, but it has spread to seemingly every startup on Earth. The internet is littered with podcasts and blog posts from people claiming this one number can solve all your company’s alignment problems.

It’s always hard to tell if a given methodology works from the outside, yet most of the content proclaiming success is made by outsiders, often as content marketing for a class or a coach or a PDF meant to generate sales leads. (The first Google result for “north star metric” is a post from a guy calling himself a Growth Hacking Coach explaining “the difference between your North Star Metric (NSM) versus One Metric That Matters (OMTM).” Talk about stinky smells!)

I realize the irony of me, a consultant, writing this. But I swear, I’m not here to make any bold claims. Instead, I want to look at the phenomenon as an ecologist would. The North Star Metric is an invasive species, spreading like a weed into places it doesn’t belong. When it blooms, it gives off a foul smell, and I notice. The ecologist in me asks, “How did this get here? What is it about the soil conditions that allowed it to take root?” I look up at the sky and judge the wind. I put my hands in the dirt.

The promise of the North Star Metric is not inherently objectionable: Product-led companies should have one metric that shows whether customers are getting value from the product. Tracking this metric, and communicating it broadly, will give disparate teams a shared point of reference.

More time spent listening to Spotify is probably a sign Spotify is delivering more value to its customers. If Spotify implemented a bunch of changes that led to people listening less, that would probably be bad for Spotify’s customers and the metric would tell us so. Fine.

A more opinionated metric seems better. Facebook may have to focus on Daily Active Users because it is so many different things to so many different people, but most teams should focus on a metric unique to them — Spotify’s listening minutes, Airbnb’s booked nights, etc. These metrics tell you what the company actually does for its customers. And because it’s closer to the ground, product teams can connect what they’re doing to the metric more directly.

If the argument for a North Star Metric were simply, “We should have a really distilled view of whether customers value our product,” I think it’s hard to object. Like most invasive species, the North Star Metric is not inherently bad; it’s more a matter of appropriate time and place. The trouble starts when the North Star Metric becomes a business concept rather than a customer concept. Now it’s an invasive weed, spreading into places it shouldn’t be.

Here’s the thing: Businesses do have a North Star Metric. It always, always, always starts with a dollar sign. Maybe it’s revenue, maybe it’s free cash flow, maybe it’s gross profit. Maybe it’s EBITDA or burn rate or earnings per share. Regardless, I can assure you that “listening minutes” is not the one and only thing Spotify cares about above all else. The business’s goal and the customers’ goal will not be the same. This seems obvious. And yet.

And yet, the dream of one metric to rule them all persists. For some reason many people think there’s a world where we can resolve tradeoffs without tension or conflict. If only we had the one metric that perfectly internalized and balanced the different considerations (and could anticipate them in advance, so the metric controlled for them!), all these difficult conversations would just melt away. Nope. Life, and business, is full of hard choices.

Of course, once you decide to design one metric that is meant to encapsulate all the choices a company may face, across both business concerns and customer concerns, you inevitably end up with something very complex. Instead of something like “gross profit” or “rooms booked” you end up with “Daily active browsers who made a purchase in the last 30 days (excluding paid search).” The metric is carefully calibrated so it can’t be gamed and it won’t be incomplete and it isn’t too volatile.

Then, in order to get the metric to stick, someone crafts a snappy name: “Engaged users.” The buzzword spreads, but no one can tell you what it actually means. Data analysts labor to maintain the esoteric calculation; the CEO ignores it; every team picks a different measure that feels actually relevant to them; and every few quarters the company breaks out into a melee over some small tweak to the definition that would require restating all the numbers but is “more aligned.” Eventually some brave executive kills the metric, tearing out the invasive plant root and stem, and a year later everyone acts like the whole embarrassing episode never happened. Then some new PM comes in and suggests, “Hey guys, I really think we need a North Star Metric,” and everyone groans.

The fundamental delusion that enables this whole cycle is the hope that there are not different stakeholders with different objectives. Sounds nice; isn’t real. The only way to resolve irreducible conflict is to surface the conflict and make a choice.

North Star sprawl seems to happen in organizations that aren’t good at conflict. Rather than make hard choices, rather than let people down, rather than pick sides, these organizations procrastinate and outsource the conflict to the details of a metric definition. But the conflict is still there, unresolved.

I see smaller versions of this problem all the time. Teams, especially those with inexperienced leaders, try to boil a decision down to a single dimension. If a decision is only being made on one dimension, there’s never any conflict, only missing data. That feels cozy.

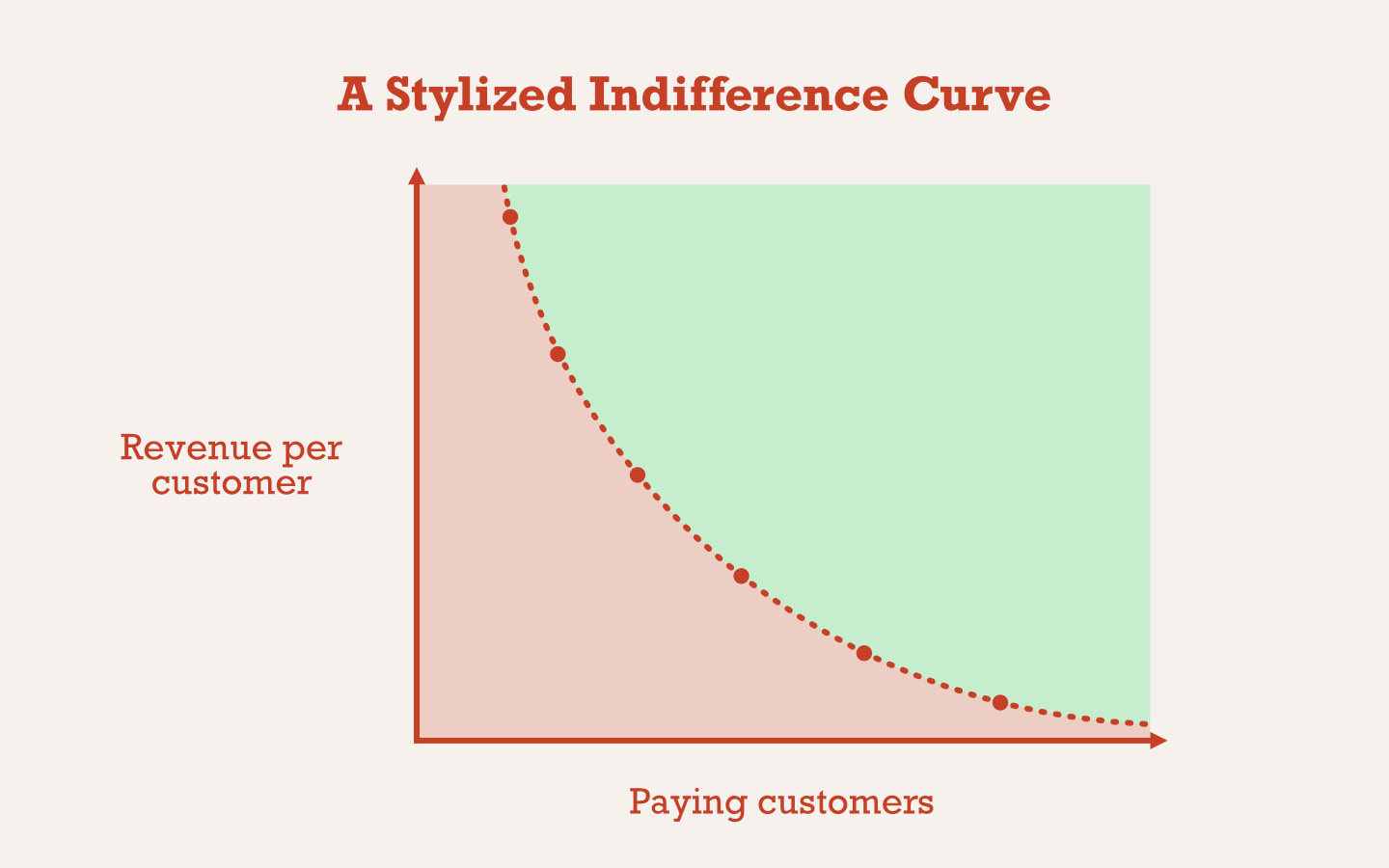

Most hard decisions are being made on multiple dimensions, and it helps to try to get it down to two. The concept I often refer to, which is very simple but can feel like a revelation, is an indifference curve. Two axes, two different metrics. You can express a preference between any two points on the plot. The boundary connecting points of equivalent value is known as the indifference curve. In the plot below, every point in the green area is preferable to any point in the red area.

When confronted with a hard decision, taking a step back and asking what the two dimensions of the decision are can be incredibly revealing. So too is asking for preferences between two points on the plot. It visualizes stakeholders’ underlying evaluation criteria. Plot enough points and the indifference curve reveals itself. Agree on this curve before evaluating real data and there’s a chance the decision becomes a lot easier when the data arrives. No more false alignment; no more stink.

This week’s recommendation is a bit of a meta-recommendation: Letterboxd. For me, 2024 has been the year of movies, and it has been really nice having a simple place to track what I’ve watched, build lists, and follow people whose judgment I trust. I’d love to follow some friends so if you’re on Letterboxd, follow me!

While I’m at it I’ll make a specific movie recommendation too: The original The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. I saw it last month at the Paris Theater, filled with New Yorkers who were laughing and cheering and just generally having a good time. Great pacing, great 1970s New York accents, great texture.

Great post. Maybe what makes the soil fertile for North Star Metric and dozens of other “methodologies” and “strategic frameworks” and “matrix management” is a deeper issue - discomfort with embracing hierarchy, management, and power.

The idea of “power” makes many folks shift uncomfortably in their seats: “if only we had magic numbers on a wall so I didn’t have to, you know, tell anyone what to do, it would all be so much easier!” Hierarchy is an ancient (and effective) technology for resolving conflict and making decisions yet we hate to use it; the result is management “outsourced” to a bunch of strategy templates / acronyms and meetings where nobody is in charge. I agree, it’s a delusion.

Just a theory!