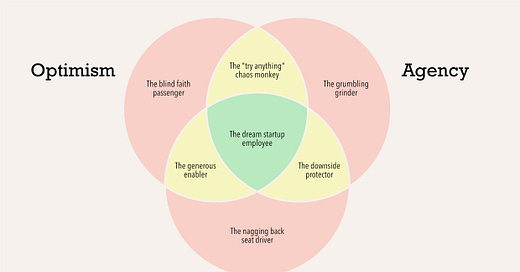

Startup employees come in types, and some are much better than others.

I’ve worked closely with hundreds of people across a handful of companies. Along the way I’ve been collecting scraps about what makes some people a joy to work with and others not, what makes some people wildly effective and others not, and what makes some people lasting participants in startup land and others not. I’ve landed on three traits that differentiate the best from the rest.

Optimism

Startups only exist in a world of irrational optimism. Most fail and the odds are terrible. But you gotta believe.

Startups suffer from a long list of afflictions; the believers are much more likely to overcome them. In many ways this reminds me of the role of the mind in medicine, where “the will to live” has a substantial effect on survival rates. Long term optimism makes it easier to accept short term failures and to reframe obstacles as opportunities.

Optimistic reframing is a real skill. It starts with temperament, but can be honed through practice. Simply forcing yourself to speak optimistic words or think optimistic thoughts will make you more optimistic. (A famous 1988 psychology study showed that participants who held the corners of their mouth upward with a pencil rated cartoons as funnier, among other things. This study has, like many others, been felled by the replication crisis, but as an optimist I choose to hold on to it.) I now pay close attention to exactly how the most optimistic people I know reframe situations, and I try to copy them.

Optimism alone is blind faith, and blind faith isn’t much help. It’s a willingness to accept things as they are, even if they’re bad, and assume everything is going to work out. It often manifests as a belief that other people or outside forces will save you. (They won’t.)

Agency

Add in agency and we’re really starting to get somewhere. Agency is a bias for action. It’s the belief that you, and you alone, can change your circumstances. It’s the willingness to roll up your sleeves and get to work to just Make. Shit. Happen.

High agency, low optimism people are rare. But those who fit this description tend to limit their scope, grinding out narrow wins while muttering complaints about the broader direction. They prize the feeling of autonomy and will go to destructive lengths to maintain it. They often try to wall themselves off from other parts of the organization to avoid meddlesome questions from other teams. They pursue agency through isolation.

High agency, high optimism people are a whirlwind. They’ll try almost anything to see what sticks. These folks are particularly valuable as a counter-balance to low agency people because they kick teams into gear. But sometimes their actions manifest as “shoot first, aim later” in a way that can be frustrating. And they have a tendency to interpret the results of their actions through rose colored glasses, which means they sometimes pursue initiatives long after it becomes clear that the juice is not worth the squeeze.

Rigor

Enter rigor. Rigor is about paying obsessive attention to what we’re doing and whether it’s working. It’s about clear thinking. It’s about an honest assessment of the situation. It’s often data-intensive, but doesn’t have to be.

People who are high on rigor but low on optimism and agency are an absolute buzzkill. They can give you a million reasons why something won’t work. They shut conversations down and their tight logic breeds doubt and inaction. They’re the backseat drivers who undermine the driver’s confidence and cause more accidents than they prevent.

High rigor and high optimism is a great combination as long as it’s paired with a teammate who’s hard-charging. High rigor, high optimism folks make amazing supporting actors, helping the lead actor shine. But without a kick in the pants, they won’t drive broader initiatives forward.

High rigor and high agency people tend to run around preventing impending messes. They think ahead about what could go wrong and go out of their way to head it off, but they ideally manage to do this without slowing everyone else down. They protect a team’s downside.

The unicorn

Some people sit right at the overlap of optimism, agency, and rigor. They make spectacular leaders and founders. But they also make ideal early stage generalists. I’ve worked with people right out of school who fit this type, and though they’re not ready to run a company yet they are definitely ready to tackle the types of pressing, gnarly problems that early stage businesses face every day.

Find these people and throw them in the deep end. Give them as much responsibility as they can handle, and then give them a little more.

Balance

Startups are teams, not a collection of individuals. What matters most is balance.

Every team sits somewhere in this Venn diagram. Great teammates have an intuitive sense of what a team needs and leans into the persona that pulls the group toward the center. If the team is long on agency and optimism but low on rigor, a great teammate will lean into their rigorous side. If the team is optimistic and rigorous but short on agency, a great teammate step up and just act to encourage a sense of agency.

Great managers assemble teams that balance these three poles. Most people lean one way or another, and assembling a team who’s natural state is balanced across optimism, agency, and rigor is the job of the manager.

Great leaders can sense where the entire organization lies in this diagram and applies pressure — through words, through action, through hiring — to move the center of gravity closer to the middle. If the org needs more agency, reward people who are high agency. If the org needs more rigor, ask questions that require rigorous answers. And if the org needs more optimism, model optimism.

This balance isn’t limited to startups, of course. Families are teams that need to balance optimism, agency, and rigor. So too are classrooms and cities and sports teams. For that matter, the same could be said of the voices in your head.