Zero-sum thinking is the enemy

“What do we need to do to make this situation positive-sum?”

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the basics of interpersonal conflict. What causes it and how can we resolve it productively? This week I’m exploring the following hunch: Lots of conflict comes down to positive-sum versus zero-sum thinking.

Two people can look at the same situation and one can see it as positive-sum, and the other as zero-sum. This mismatch produces very different behaviors. If you and your partner can both see that a situation has positive-sum potential, you become collaborators instead of competitors.

A basic diagnostic

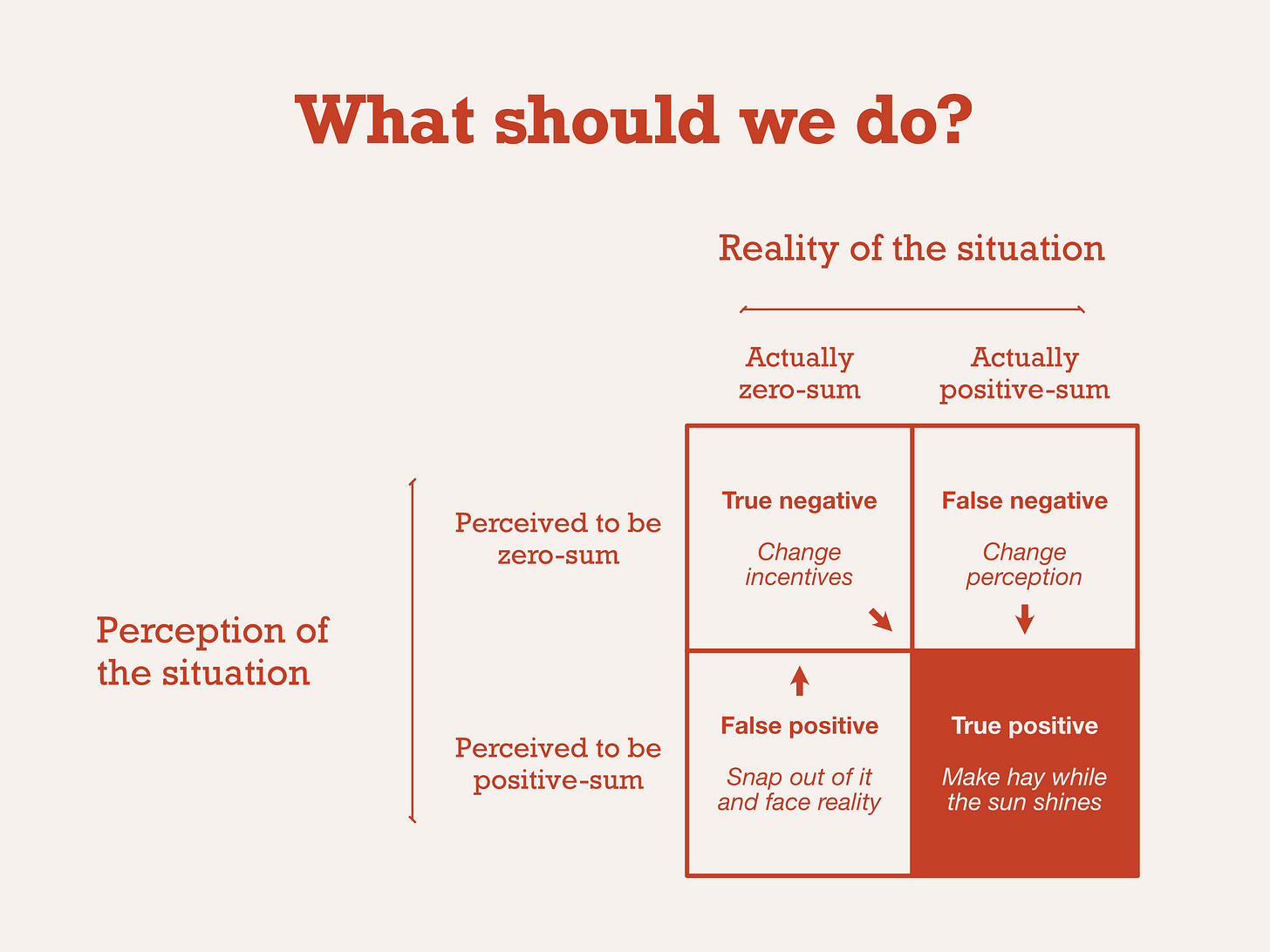

If I think a lot of unproductive conflict is rooted in zero-sum thinking or situations, what tools can help fix that? Here’s one simple attempt:

You and your partner can use this little 2x2 to run some diagnostic tests on the conflict. Any given situation can be placed into one of these four squares. Each square has an implied action, too:

Together you can ask: “What do we need to do to make this situation positive-sum?” This sounds stupidly simple, and maybe it is. But it is the question to ask when you find yourself in conflict.

If you and your partner diagnose the situation differently, this clarifies how you need to change their thinking or behavior.

A few observations in no particular order

This grid is also useful at the individual level. Sometimes I just get up on the wrong side of the bed and walk around sulking. I’ll be in a good situation and it’ll feel like a bad one without justification. So I take a step back: This feels bad, but is it? No? Okay, sounds like I just need a change in perception. (If instead the answer is, “No, this really is bad,” then I need to either accept that and sit with the discomfort or I need to escape the situation entirely.)

You can choose where to spend your time. You should try to spend most of it in situations that are positive-sum.

But you shouldn’t spend all your time there. Some situations are bad, yet you need to be there to make them just a little bit better. To avoid these situations is to live a life blissfully in denial — until it catches up with you. People will rightly perceive you as avoidant, as unwilling to do the hard work of confronting fundamentally flawed situations.

When I wrote “change incentives” into the True Negative square, I couldn’t help but think about the famous prisoner’s dilemma and Tit for Tat, which is a great example of how changing incentives can change a situation from negative sum to positive sum.

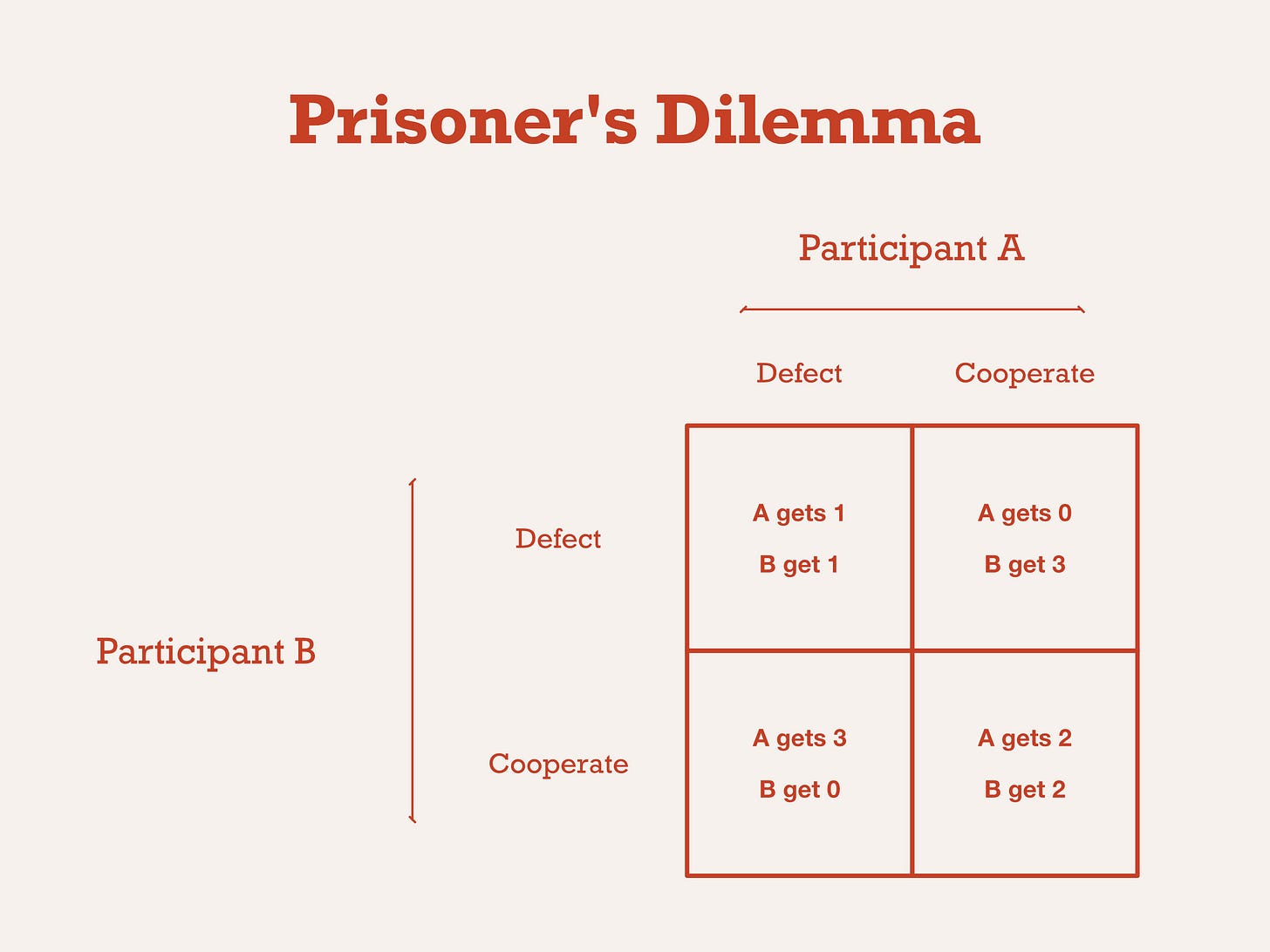

The prisoner’s dilemma was invented at Princeton in the 1950s and was one of the earliest examples of the new field of game theory. The game is simple: Two participants play the game together, once. The participants each have two choices: Either defect or cooperate. Each choice, when paired with the choice of the other participant, yields a reward. The highest reward is if you choose to defect and your partner cooperates — they get nothing and you get more. If you both cooperate you get a bit less individually, but more in combination. If you both defect you both get nothing. The participants can’t communicate with each other.

The reason this is a dilemma is it’s not clear whether to cooperate and risk getting stabbed in the back, or to defect and risk getting nothing. Knowing nothing about your partner, the expected value is higher to defect. You’ll only feel comfortable cooperating if you know where your fellow prisoner sits on this little spectrum:

In 1980, a professor set up a computer tournament to try to find the best approach to the dilemma. Teams programmed little bots, and the bots competed against each other in many rounds of the game. The winner was a bot called Tit for Tat, which always cooperated in Game 1, and then in Game 2 matched the strategy that its opponent used in Game 1. This approach encourages cooperation.

Tit for Tat changed the incentives for its opponents in a way that made the positive-sum outcome easier to reach. The result: More, on average, for everyone. New incentives, better outcomes.

One of the reasons I love working with startups is that they are largely understood internally to be positive-sum ventures. It’s very hard for an individual to get ahead without the company succeeding too. Equity compensation further reinforces this. Cooperation is the name of the game.

Once a company stops growing, it’s much harder to convince people it’s a positive-sum endeavor. Politics and pettiness spread. Growth encourages selflessness which encourages growth with encourages selflessness, until the company’s growth begins to slow.

The appropriate leadership approach depends on which cell you find yourself in. Sometimes you need to redesign incentives so the team will behave differently. Sometimes you know the situation is positive-sum but no one else does, and your job is to help them see the light (ie “winning hearts and minds”). Sometimes the incentives are right and everyone knows it, and all you have to do is keep things on track and increase the speed. Step 1, in all these cases, is a diagnosis of where things stand in the 2x2.

Choosing a leader should start with using the 2x2 too. Some leaders are best at figuring out how to fix incentives, and they should be placed into situations where that’s the problem to solve. Others are great and taking things that are already working and making them bigger, faster, stronger. If you’re picking a leader you need to think carefully about what the situation needs and what each candidate can provide.

Interesting side note on Tit for Tat strategy in practice:

For Wharton MBA negotiations courses, we used to have teams play a game that is essentially a repeat Prisoner's Dilemma: two teams would have to set their prices for selling "oil", and decide whether to "collude" or "defect" from an oligopoly scheme with the usual 2 x 2 PD grid of payouts.

BUT we would add some very realistic noise into the perceived outcomes - so sometimes teams could get a bad payoff even from colluding.

Lots of teams knew about Tit for Tat and tried to apply it. These were Wharton MBAs after all! But even when they were forewarned about the imperfect payoff signal, Tit for Tat was a disaster. The noisy outcomes would lead teams to punish each other left and right for misperceived violations, and trust would break down.